June 13, 2005

Feature

Input Data, Please:

Does File-sharing Really Hurt the Television Industry?

If you follow the entertainment news, you know that the big media companies are really worried about filesharing and copyright violations. If you're a computer geek, you know something about the technical side of filesharing. And if you're a television fan with a broadband connection, you may be one of the tens of thousands of people who share television episodes, in blatant violation of copyright. (If you have no idea what BitTorrent is, and think "filesharing" is when a coworker drops his manila folders on your desk, go read the last half-dozen issues of Wired and then get back to me.)

| What I am going to argue is that, well, that genie's out of the bottle, and before trying to force it back in, maybe we should figure out what kind of damage the genie is actually doing. |

I saw an article recently that said the television industry, as currently constructed, was going to crumble within 10 years. It's clearly in desperate need of a new business model; if the networks and multinational corporations that own them want the television industry to survive, they have to make filesharing less attractive. Not by suing the folks distributing the files, which will only drive advances in file-sharing technology, designed to get around the legal constraints (which is basically why the peer-to-peer networks work the way they do now), but by making access to content easy and attractive.

So what's the solution? Got me. I think it would be helpful if someone calculated the actual financial damage to the television industry from P2P filesharing. I see all these people racing around like Kermit before the start of every Muppet Show, convinced the whole assembly is going to collapse, and while I think that it's possible that's true, I want data.

Let me repeat: public policy should be based on actual data. As a result, here's some of the questions I think we need to answer first.

Are people more likely to download television shows than (a) watch broadcast; or (b) wait for DVDs?

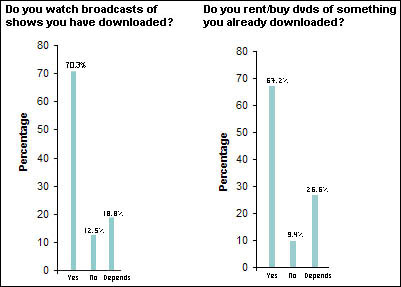

While writing this column, I did a completely unscientific survey of the people in one online community: this is what I learned.

|

70% of those who download also watch the broadcast.

67% of those who download also buy or rent the DVDs.

And over 50% of those who download do so because they can't get the show any other way.

Now, this is a limited and unscientific sample of people who are into television, but what we're seeing is that of those who download, fewer than 1/3 download instead of watching the broadcast. Most do both, and some download, watch the broadcast, and buy the DVDs.

We'll get into some reasons why later on.

What percentage of the viewing audience is lost to advertising from filesharing?

Okay, tens of thousands of people are downloading episodes. How many, exactly? And how many people are watching live? How many of those who download are also watching live?

How much of the potential audience is making the effort to actually download? Downloaders tend to be dedicated fans, not casual viewers of a show, because while downloading's become fairly simple, it's not as easy as turning on the television and plopping onto the couch. But networks and advertisers aren't very interested in dedicated fans; they want casual viewers, because the casual viewers on any given evening far outnumber the dedicated fans. If that holds true, then what's the real damage done as a result of downloading?

And by "real damage", I mean actual financial data. Do downloads make the ratings go down? Do the advertisers suffer financial losses? Do the networks suffer losses? I know that if a show fails to deliver its target audience to advertisers, the network has to pay the advertisers back for some of their costs. Has this happened yet as a result of downloading? Is anyone collecting this data?

The obvious corollary to the above question is, Does the overall viewing audience grow as a result of filesharing?

I know, this avoids the moral issues entirely by claiming copyright violation is okay if it increases the audience for a product, but there is some support for this position.

For instance, there's a huge pimping campaign for House going on in some online communities; I could download, for free, the first 3 episodes of House if I wanted to. If I then liked it, I would probably stop downloading and just watch it on live TV. What is the difference between that fan-level distribution and the Sci-Fi Channel making available episode 101 of Battlestar Galactica for download? The network must know that that file is going to be redistributed far and wide. It's a calculated part of their marketing strategy. Sadly, the production company grossly underestimated the huge US audience for the show, and made themselves look silly by squawking about Americans downloading the entire UK run (because the entire run aired in the UK months ago, oops) at the same time the network had the first episode available for free download.

| Galactica became the Sci-Fi Channel's newest hit in part because people were able to download it, see the quality, and spread the word before the show actually aired. |

If filesharing damages broadcast distribution finances, what does it do to DVD sales?

If you believe the results of my survey above, the people most likely to download are among the people most likely to buy DVDs. Does filesharing help or hinder the development of that market? It's possible it hinders the market, but those most interested in DVDs are also most interested in the extras that come with them: the commentaries, the blooper reels, the interviews. These materials are rarely provided with downloaded episodes, since they are added long after the original episodes air.

So, why do people download?

The primary reasons seem to be: because they missed an episode (71%); because it's airing in another country and they won't see it soon (69%); or because it's airing in another country and they won't ever get to see it (51%). Other reasons people download are because it's not being broadcast and it's not out on DVD (56%); because they wanted a permanent copy (31%); because it was on pay cable (30%); and because it's easier than finding time to watch when the show was actually on (27%). In short, most people download because they can't get it any other way.

When people like a television show, they want all of it, and they want it now. So if, for instance, your American distributor cuts 18 minutes per episode from the original BBC hour-long show, people will download the files in order to see the complete version (A&E aired the edited version of Spooks as MI-5 in the US). If your cliffhanger is resolved in the UK months before the US, people will download (Sci-Fi Channel did this consistently with Farscape). If the BBC airs a provocative documentary about terrorism and international politics that is never going to air in the US, people will download it (The Power of Nightmares: British friends tells me it's fabulous). The problem goes the other way, as well: British and Australian television fans either can't get at all, or can only get very edited versions of American shows they want. So they download.

The wealthier viewers can afford to pay for content. They can join Netflix, or pay for HBO in order to watch Deadwood and The Sopranos. But there are people out there who can't afford HBO and who want to watch Deadwood anyway. If you're paying $40/month for DSL already, or if you're a college student on a limited income but with free T3 access, and you can get free HBO content that way, why would you bother subscribing?

Conclusions

The choice of whether to download depends on convenience and completeness.

If it's easy to catch it on broadcast, and the viewer knows they're getting

everything that would have been available on download, they'll go with the

broadcast. If they're getting better quality on a DVD, or interesting extras

on a DVD, they'll get the DVD. With broadcast or DVD, they're also spared

the occasional file-compatibility Episode , where the downloaded file won't play

on their media software. And, finally, they're less likely to download if

they know they won't have the story be spoiled for them accidentally before

they get a chance to see it, which is a result of internationally-staggered

distribution schedules.

None of that really takes into account the legal issues. If an ISP notices someone using BitTorrent to download an episode of The West Wing, they can threaten to cut off that person's internet access. They would be within their rights to do so, because torrenting means the data stream is going both directions, and uploading copyrighted materials is illegal. Most people would probably stop filesharing at that point, but the entire system of filesharing isn't going to go away that easily. The software will evolve to survive, in spite of the networks and whatever legal action they take. It's far too convenient, and it's free, and the combination of the two is what's driving the popularity of P2P systems.

So if we can get answers to some of the questions above, and find out what effect the downloading phenomenon is actually having, that may help determine whether the system actually needs fixing, and if so, what form that fix should take. If filesharing is causing actual financial damage, then the networks should take action. Not by suing their audience, but by making it more attractive for the audience to get their shows from the networks than from the filesharers. And for that, they need to understand why filesharing is so popular in the first place.

Further reading:

Michael Geist dissects the Canadian music industry's

claims that

file-sharing is damaging their sales in

Piercing the peer-to-peer myths: An examination of

the Canadian

experience, in First Monday, volume 10,

number 4 (April

2005). He finds that shrinking CD sales can be

blamed on rises in DVD

sales (thus less shelf-space for CDs in the big

retail outlets), the

overall reduction in the amount of time people spend

listening to

music, changes in the music retail and distribution

market associated

with big-box retail, and broad dips in the economy as

a whole.

Mark Pesce discusses the Battlestar Galactica Episode in Piracy is Good? How Battlestar Galactica Killed Broadcast TV, in Mindjack, May 13, 2005.

Email the author.

All written content © 2005 by the authors. For more information, contact homer@smrt-tv.com